CHRISTIANS CONTRIBUTION TO ART AND ARCHITECTURE: A GLOBAL REVIEW

Dr. R. Xavier

Assistant Professor, Department of History

Loyola College,

Chennai

Key Concepts: Apse, Christian Basilica, Renaissance

By the beginning of the fourth century, the ism of Christianity started growing as a religion of mystery in the cities of the Roman world. It was attracting converts from different social levels. Christian theology and art was more and more enriched due to its' cultural interaction with the Greco-Roman world. Christianity was radically transformed through the actions of a single man as in 312, the Emperor Constantine defeated his principal rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Neither the Imperial Rome nor the Christianity remained the same after this victory. Rome became a Christian country, and Christianity took on the aura of the Imperial Rome as after that victory, Emperor Constantine became the principal patron of Christianity.

In 313, Constantine issued the Edict of Milan which granted religious toleration to all the subjects in his country. Following this, though Christianity could not become the official religion of the Rome until the end of the 4th century, Constantine's imperial sanction of Christianity on the whole, transformed its' status and nature.

The transformation of Christianity in Rome, is dramatically evident through a comparison between the architecture of the pre-Constantine church and that of the Constantine and post-Constantine church. During the pre-Constantine period, the distinction of the Christian churches was not much different from that of the typical domestic architecture, but, this domestic architecture obviously was unable to meet the needs of the Constantine's architects.

Emperors of Rome apprehended the construction of temples as the testament to their pietas or as the respect for their customary religious practices and traditions. So, it was natural for the Emperor Constantine to construct edifices to propagate Christianity. He built churches in Rome including the Church of the renowned St. Peter. Along with the churches which he built in his newly constructed capital of Constantinople, he also built churches in Holy Lands i.e., the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

The temple architecture of Rome was largely followed in the exterior architecture of the Churches. Since Christianity was then considered as the religion of mystery, it demanded greater initiation to participate in the religious practices and so the Christian architecture laid greater emphasis on the interior.

Other reasons for the construction of such larger interiors during those days in the Christian churches, was to house the growing congregations and to mark the clear separation of the faithful from the unfaithful. Also, another need of that day was that the new Christian churches were also to be visually meaningful because, the buildings

needed to convey the new growing authority of the Christianity. These factors were instrumental in the formulation of this kind of architecture during the Constantine period and this soon became the core of the Christian architecture of the Christian Basilica from then onwards till our own time. (Farber, www.khanacademy.org)

THE CHRISTIAN BASILICA

The basilica was not a new architectural form. The Romans had been building basilicas in their cities as part of their palace complexes for centuries. Basilicas had diverse functions but essentially they served as formal public meeting places. One of the major activities carried out at the basilicas was its' usage as the apt site as the law courts. These were housed in an architectural form known as the apse. (Fletcher Banister 2001, 39).

ARCHITECTURAL STYLES THE EARLY CHRISTIAN

The period of architecture termed Early or Paleo-Christian lasted from the first Christian Church buildings of the early 4th century until the development of a distinct Byzantine style which emerged in the reign of the Emperor Justinian I in the 6th century, rather than with the removal of the seat of the Roman Empire to Byzantium by the Emperor Constantine in 330 CE. In Armenia, where Christianity became the official religion in 301, some of the earliest elegant Christian churches were constructed (Pinto Pio. V 1975, 12).

THE BYZANTINE

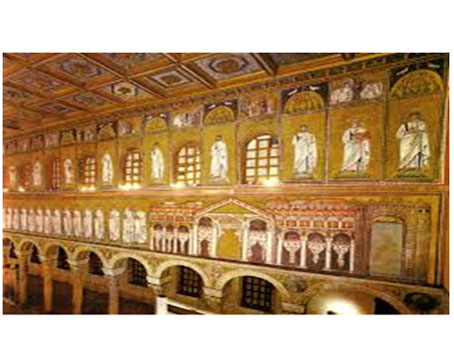

Ravenna, being situated on the Eastern coast of Italy, is a home for several vast churches consisting of a basilica plan dating back to the age of the Emperor Justinian (6th century CE). San Apollinaire Nuevo is in plan similar to Santa Maria Maggiore, but the details of the carvings are no longer in the classical Roman style.The capitals of this church resembles fat lacy stone cushions. Many of the mosaics constructed during those days are intact till date (Rene Huyghe 1981. 60).

San Apolliniare Nuevo

THE ROMANESQUE

After the decline of the Roman Empire, the building of large churches in Western Europe gradually gained momentum with the spread of organized monasticism under the rule of Saint Benedict and others. A huge monastery at Cluny, only a fraction of which still exists, was built using a simplified Roman style, stout columns, thick walls, small window openings and semi-circular arches. The style spread along with monasticism throughout Europe. The technique of building high vaults in masonry was also revived.

Curing of decoration evolved that had elements drawn from local Pre- Christian traditions which incorporated zigzags, spirals and fierce animal heads. Also, the typical wall decorations were painted with murals and soon the Romanesque building techniques spread to England along with the Norman Conquest (Rolf Toman 2010. 75).

THE GOTHIC

By the mid 12th century, many large cathedrals and abbey churches had been constructed. Since this required the engineering skills to build high arches, stone vaults, tall towers and the like, they were also well developed. As a result, the style evolved to one that was less heavy, had larger windows, lighter-weight vaulting supported on stone ribs and above all, the pointed arch which is the defining characteristic of the style now known as Gothic.

With thinner walls, larger windows and high pointed arched vaults, the distinctive flying buttresses developed as a means of support. In this unique style, the huge windows were ornamented with stone tracery and filled with stained glass illustrating the stories from the Bible and the lives of the Saints (Swaan Wim 1985. 33)

THE RENAISSANCE

In the early 15th century a competition was held in Florence for a plan to roof the central crossing of the huge, unfinished Gothic Cathedral. It was won by the artist Brunelleschi who, inspired by the domes that he had seen during his travels, such as that of San Vitale in Ravenna and the enormous dome of the Roman period which roofed the Pantheon, designed a huge dome which is regarded as the first building of the Renaissance period. Its style, visually however, is ribbed and pointed and purely Gothic. It marked the advent of the Renaissance (a rebirth) in its audacity, excepting the fact that it looked back to Roman structural techniques.

Brunelleschi, and others like him, developed a passion for the highly refined style of Roman architecture, in which the forms and decorations followed rules of placement and proportion that had long been neglected. They also strived to rediscover and apply these rules in other constructions which marked it as the time of architectural theorizing and experimentation. Brunelleschi built two large churches i.e., San Lorenzo's and Santo Spirito in Florence demonstrating how the new style could be applied.

Santo Spirito in Florence

These churches appealingly consisted rows of cylindrical columns, Corinthian capitals, entablatures, semi-circular arches and apsidal chapels (Gibbs Smith Lees- Milne and James 1967. 72).

THE BAROQUE

Soon, the Rococo style evolved which is a late evolution of the Baroque architecture that is first apparent in French domestic architecture and design. It is distinguished by the asymmetry found within its decoration, generally taking the form of ornate sculptured cartouches or borders. These decorations are loosely based on organic objects, particularly seashells and plant growth and also on the other natural forms that have an apparent "organized chaos" such as waves of clouds. The churches that are thus decorated have strongly Baroque architectural form but a general lightness and delicacy in appearance which is sometimes described as "playfulness" (Pevsner Nikolaus 2009. 72).

THE REVIVALISM

The 18th and 19th centuries were a time of expansion and colonization by the Western Europeans. There was also much industrialization and the growth of towns. It was also a time of much Christian revival and in England, a considerable growth took place in the Roman Catholic Church. This led to the need for new churches and Cathedrals. During those days, the Medieval styles and particularly Gothic, were considered as the most pertinent for the building of new cathedrals, both in Europe and in the Colonies (Alen and Taylor-Clefton 1989. 12).

THE MODERN TREND

During the beginning of the 20th century, building style adopted during the middle ages still continued, but in a stripped-down, cleanly functional form, often in brick. A fine example for this is the Guildford Cathedral in England. Another is Armidale Anglican Cathedral situated in Australia (Alen and Taylor-Clefton 1989. 15).

CHRISTIAN ARCHITECTURE IN INDIA

There is no art or architecture - no socio-cultural formations of any significance, anywhere in the world - relating to a nation, a region, a religious or racial or linguistic group - that is fully local or indigenous. The art and architecture of India - secular or religious - is no exception. Thus, Church art and architecture of India from the commencement of the Christian presence on these coasts at the dawn of the Christian era have been to a greater or lesser degree influenced by those of other nations and religions as they in turn have been influenced by India’s wealth of artistic and architectural traditions.

All the nations and cultures that came into contact with India - the Egyptians, the Phoenicians, the Greeks, the Romans, the Mughals, the Parthians, the Iranians, the Arabs (of Pagan, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic persuasions) and the Europeans of a later date including the Portuguese, the Dutch, the Danes, the French, and the English have all left their mark on the society and culture of India, as has also been done by the eastern countries and cultures.

There are a large number of items of artistic and architectural significance in the religious and domestic/civil life of the Indian Christians which come under one or more of the divisions and categories adumbrated above. Consequentially, in the churches there are so many types of roofs, ceilings, facades, porticos, verandahs, naves, chancels, altars, altarpieces, statues, candlesticks, pillars, doors, doorways, architraves, pulpits, crosses, cross pedestals, chalices, censers, censer-boats, bells, belfries, books, book-illustrations, and bookmarks, bibles and bible stands, choirs, tabernacles, monstrance, railings, wall paintings, wooden panels, cloth paintings, vestments, beams, rafters, processional umbrellas, canopies, chariots,... and a thousand and one other objects to be considered (John Menachery, Tripod.org.

REFERENCES

-

Banister Fletcher, 2001. A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, New York: Elsevier Science & Technology.

-

Pio V. Pinto, 1975. The Pilgrim's Guide to Rome, New York: Harper & Row.

-

Huyghe Rene, 1981. Larousse Encyclopedia of Byzantine and Medieval Art, Portland: Excalibur Books.

-

Toman Rolf, 2010. Romanesque – Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Potsdam: HF ulmann.

-

Wim Swaan, 1985. The Gothic Cathedral, London: Park Lane Printing & Publishing House Ltd.

-

James Lees-Milne, 1967. Saint Peter's: The Story of Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, London: Hamish Hamilton.

-

Nikolaus Pevsner, 2009. An Outline of European Architecture, Layton: Gibbs Smith.

-

Clifton-Taylor, Alec, 1989. The Cathedrals of England, London: Thames & Hudson.

Menachery John, Tripod.org

Recent Artcles